“Plot is a Fascist Construct”

On Matthew Salesses’ Craft in the Real World and Why Most Writing Books Suck

“If we can admit by now that history is about who has the power to write history, we should be able to admit the same of craft. Craft is about who has the power to write stories, what stories are historicized and who historicizes them, who gets to write literature and folklore, whose writing is important to whom, in what context.”

- Matthew Salesses, Craft in the Real World

Stephen King haunts me.

I don’t mean that literally, although it would be in his wheelhouse. No, King haunts me through one particular object: His 2000 memoir-cum-writing manual, On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft. According to Goodreads, I read it in November 2017, the same month I officially began my consistent fiction writing practice.

Although I always knew I was good at writing, I long thought this would take the form of music journalism. In my teenage years and early 20s, I wrote zines and reviewed albums and shows. It was only after I graduated from university did I realize that I actually wanted to pursue a more creative form of writing, never mind the fact that music journalism jobs literally do not exist anymore. Without much formal instruction to learn from–I took exactly one creative writing workshop in undergrad–I sought out craft books, filled with advice from older writers who surely knew better than I, a bébé.

I read the classics, Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird and William Zinsser’s On Writing Well, as well as newer texts like Shawn Coyne’s The Story Grid, and Louise DeSalvo’s The Art of Slow Writing. Still, it was King’s On Writing that was to be the real thorn in my side. It’s not like it’s a bad book–at the time, I gave it a five-star rating. But it did have some fucking bad advice in it that haunted me for years.

“You’re allowed to take one day off writing a week,” King wrote. I internalized this, thinking it was a standard I must also hold myself to, while also working retail full-time. Despite my best efforts, I never seemed to be able to write more than three or four days a week. Stephen King would think I’m a failure! It took me a long time to realize that King was giving advice from his perspective and experience. Even when he was working as a teacher by day and writing the manuscript for Carrie at night, he was still a straight white dude living in the United States during the early ‘70s with a wife to take care of him and their children. King, I realized, was writing from a certain position. The advice he had about writing wasn’t actually objective but rooted firmly in place and privilege.

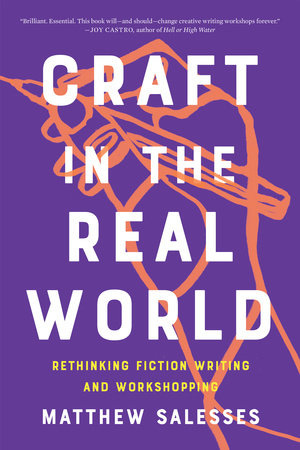

Matthew Salesses’ new book Craft In The Real World: Rethinking Fiction Writing and Workshopping, published last month by ever-excellent Catapult, articulates so much of what I realized after being disappointed over and over again by the horrible advice of most craft books. At a virtual book launch hosted by New York City bookstore McNally Jackson, one of the first things moderator and writer Brandon Taylor said was, “Some craft books I finish and I can’t wait to write, while I finish other craft books that make me never want to write again.” Salesses said he read 50 to 100 craft books as research for his own work. “And I hated almost all of them,” he stated, saying he was reluctant to read them in the first place, already knowing what he would find.

Reading Craft in the Real World, I couldn’t believe that no writer had dared before to articulate everything wrong with how creative writing is taught. At the launch, Salesses said, “I waited fifteen years for this kind of book to come out before I decided to write it myself.” It is a book I read with one hand on the page and the other on a highlighter with its cap off–almost every third page of my copy has some kind of neon marking on it, as if to say, “You must remember this.”

Craft in the Real World is divided into three parts. The first, “Fiction in the Real World,” deconstructs the myth of pure craft and redefines craft terms. The second, “Workshop in the Real World,” argues against the power imbalances of the conventional writing workshop structure. The third is a series of exercises for revision.

In the first section, the essay “Redefining Craft Terms” questions what exactly we’re talking about when we talk about writing. What does it actually mean when writers and readers talk about tone, characterization, and stakes? Salesses argues that hegemonic Western notions of plot and conflict often assume that the characters have the most agency over their lives, while any marginalized person can tell you that most things about the world - how they interact with it and how others interact with them - are completely out of their control. “Agency, the way we talk about it in fiction, is really just privilege,” Salesses stated at the launch. “My life is not like that.” (Taylor agreed, stating, “Plot is a fascist construct.”)

The second half of the book focuses on how the structure of the writing workshop fails marginalized writers. In a conventional workshop, writers are forced to sit in silence while the rest of the participants critique the work, without ever asking the writer what their intention or goals for the piece are, adhering to the (biased) belief that a text, even one in its very beginning stages of existence, should speak for itself.

In the essay “The Reader vs. POC,” Salesses describes how this structure fails Black, Indigenous, and writers of colour in particular. Oftentimes, a majority white workshop will blindly assume that stories are exclusively meant to be written for a white audience. If the text is not “relatable” or “believable” to the workshop, it should be changed to be easier for “readers” to understand, despite the fact that the workshop almost never takes into account who exactly “the reader” is supposed to be. Taking on this idea of relatability, Salesses writes, “To say a work of fiction is unrelatable is to say, I am not the implied audience, so I refuse to engage with the choices the author has made.”

In the last section, Salesses suggests a number of changes that can be made to the workshop structure, such as submitting “Writing Notes” alongside the piece that explain the thought process behind certain craft decisions, or workshop participants offering only questions, suggestions, and observations to a piece in place of critiques.

Overall, in Craft in the Real World, Salesses has written a craft book that not only acknowledges where it is coming from, but where writing as a whole can and should go next.

Read an excerpt from Craft in the Real World here.

***

I wanted to acknowledge that as many bad writing books as I’ve read, there are a handful that have been invaluable to me as a self-taught creative writer. You have to wade through the shit to get to the flowers! Here is a list of books about writing that I’ve found actually useful:

Gotham Writer’s Workshop: Writing Fiction edited by Alexander Steele (Bloomsbury, 2003): I came across this book for the first time at the library and soon after bought a copy for myself. The book is divided into ten parts, with each chapter focusing on a different element of craft like dialogue and point-of-view. When I first started developing my creative writing practice, the exercises in this book were practical guides to get me started.

Revising Your Novel by Janice Hardy (Self-published, 2016): After a year into my writing practice of dicking around with melodramatic short stories and a bad romance novella, I decided to just say “FUCK IT!” and go for the big guns by writing a novel I had the idea of for years. After I wrote the first draft, I was super proud of myself. I wrote a novel! Reality hit when I returned to that draft a few months later, having no idea how to go about revising a multi-thousand-word project. This book helped me think through revision by posing a lot of self-guided questions about theme, character, and setting.

Before and After The Book Deal by Courtney Maum (Catapult, 2020): This book freed me. In it, Maum writes truthfully about what it means to be a writer today and how most people simply can’t dedicate most of their time to it. Her saying that she only does creative writing two days a week absolutely liberated me (FUCK YOU, STEPHEN KING, COURTNEY MAUM SAYS I ONLY HAVE TO WRITE TWO DAYS A WEEK). That being said, it is a lot more about the publishing side of things than it is the craft of writing, so unless you already have a draft of a manuscript in the works, it would probably be pretty overwhelming to read. Still, this is a really invaluable guide if you have a draft finished or a serious project you are working towards – I found the advice on the agent process and advances particularly illuminating.

***

What Else I’m Reading: I’m in the middle of Outlawed by Anna North, a recently published queer reinterpretation of the cowboy novel. I also completely lost my mind reading this article by Patricia Lockwood on Elena Ferrante.

What I’m Listening To: I’ve had two very gay and very embarrassing songs stuck in my head on a loop for the past week: The 10-year anniversary remix of “Friday” by Rebecca Black and the United Kingdoll’s version of RuPaul’s “UK, Hun?” from the recent episode of Drag Race UK, which is apparently charting?!

What I’m Watching: After months of sleeping on it, I finally watched Euphoria and loved it. Contemplating going back to school to do a thesis called “Bitch, This Isn’t The ‘80s: Modern Graphic Eyeliner and Queer Signalling on HBO’s Euphoria.” I also loved Casey Plett’s recent, spoiler-filled article for Xtra Magazine about the character of Jules and what it means for the show to depict a young trans woman into women.

What I’m Writing: Speaking of Xtra, I recently published an article for them about how my cooking group chat has provided me with connection and friendship throughout the pandemic. Read it here. I also cracked 100,000 words on the second draft of my novel yesterday and feel incredibly proud of myself for sticking with my self-taught practice for the past three and a half years.

Mutual Aid Call: The Ottawa Black Diaspora Coalition put out a mutual aid call for e-transfers to help a local Black woman avoid eviction. Check out the post here and send some money if you can.

***

Thanks for reading. If you liked this newsletter, please subscribe, like, comment and share. The next issue will be out around March 3. Take care of yourself, and each other.

"Even when he was working as a teacher by day and writing the manuscript for Carrie at night, he was still a straight white dude living in the United States during the early ‘70s with a wife to take care of him and their children"

When I was studying Descartes back in college, I thought, where did this guy find the time to sit in an oven and come up with cartesian philosophy? And I've been saying for years, decades, possibly (this was back in the 90s), all these guys weren't washing their own clothes, cleaning their own houses or cooking their own food! They had wives and/or servants. Of course they had time. And this totally explains how few women philosophers they were competing with.

congrats on your thing in xtra, it's delightful!