I Read a 400-Page Book in a Week

Get ready to binge Emily Nussbaum's history of reality television

Every Wednesday night, since I was five years old, there was a ritual in my house. At 7:59, my family would race to the basement, turn on the TV and turn off the lights. We’d nestle beside each other on the couch as a familiar theme song boomed from the speakers. If my sister and I started chatting, we were instantly shushed. “No talking!” my mom would yell. “Survivor’s on.”

Survivor was the beginning of my lifelong infatuation with reality television. The rest of my childhood was filled with a variety of family-friendly competition shows: American Idol, The Amazing Race, Dancing with the Stars. During my tween and teen years, my tastes branched more into lifestyle content, catching episodes of What Not to Wear and The Millionaire Matchmaker whenever I could.

My obsession with the genre has only become stronger in my adult life. Thanks to the streaming era’s proliferation of back catalogue content, I have seen almost every season of popular programs like RuPaul’s Drag Race and The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills, as well as D-list series that I don’t think any other human has ever completed like Siesta Key, FBoy Island and Ink Master.

Given this personal history, I was over the moon to discover Emily Nussbaum’s recently published work on the genre, Cue the Sun! The Invention of Reality TV. Nussbaum is a Pulitzer-winning television critic for The New Yorker. I first discovered her writing from her 2019 collection of criticism, I Like to Watch: Arguing My Way Through the TV Revolution, which focuses on narrative shows of the peak TV boom like The Sopranos, Sex and the City and Mad Men.

In Cue the Sun!, however, Nussbaum takes on a form of television that has more often been ridiculed than lauded. Taking its title from the ending of The Truman Show, the book details the history and origins of reality television through 13 chronologically structured chapters spanning the scope of 60 years. Despite its nearly 400 pages, I binged the book in only a week; it went down as smoothly as a new season of Selling Sunset, although it was much more informative (sorry Crishell!).

While there have been many academic and journalistic works about specific reality programs, Cue the Sun! is arguably one of the first to comprehensively detail the evolution of reality television as its own genre. The book is divided into three sections: the historical precursors for reality TV from the 1940s to the 1960s, its initial programs from the 1970s to the 1990s, and its later explosion in the early 2000s.

In the first section, Nussbaum shows how the roots of reality television begin nearly 50 years before its mainstream boom through audience participation radio programs of the late 1940s, where the public would call in and chat about their lives or participate in quizzes. These programs eventually standardized into subgenres that would become staples for reality programming, such as prank shows, dating shows and court shows. For instance, one of the most famous audience participation radio shows was Candid Microphone, a prank show created by Alan Funt that would later evolve into the TV series Candid Camera.

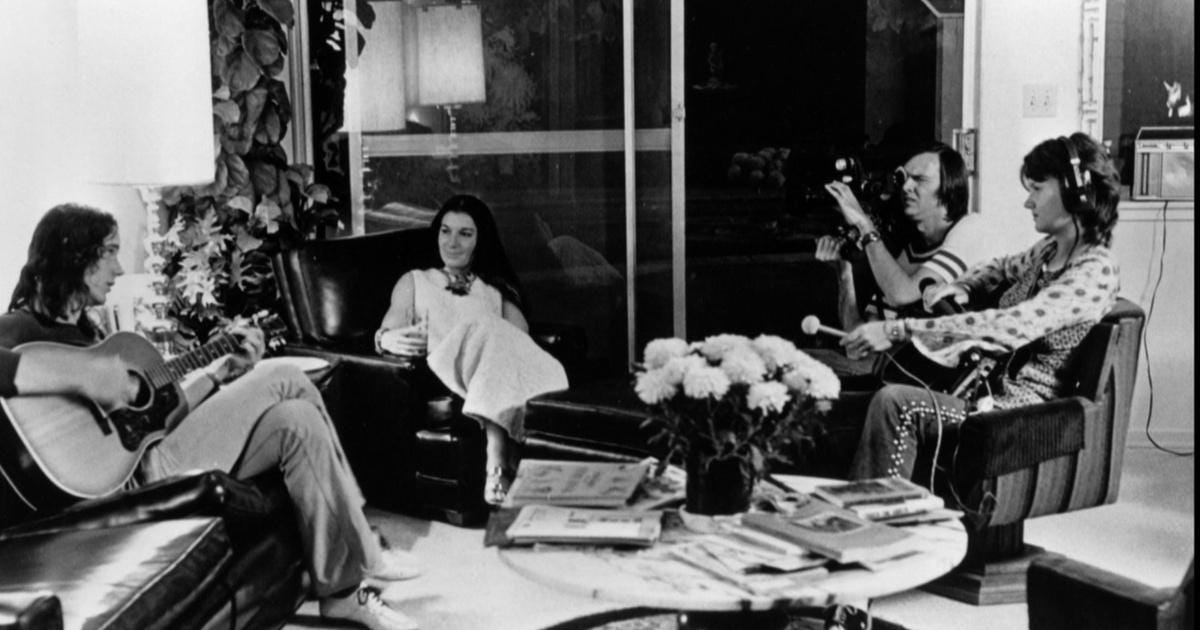

Still, the first show to be considered a reality program as we know the genre today is An American Family, a series from the early ‘70s that follows a California family named the Louds. Influenced by cinema vérité, which sought to portray subjects as purely as possible without any narration, the program was considered innovative for breaking social taboos of the time by portraying the parents’ divorce on camera and featuring an out gay son, Lance Loud.

The theme of representation of queerness comes up often in the book, which is unsurprising for a genre that has many devoted LGBTQ+ fans and defenders. Due to its reputation as “dirty documentary,” reality TV programs were some of the first American series to feature popular representations of gay men, from The Real World’s Pedro Zamora to Survivor’s first winner Richard Hatch.

Nussbaum also emphasizes how several of the most popular reality franchises have been created and produced by gay men themselves, including Charlie Parsons, the creator of Survivor, and Jon Murray, co-creator of The Real World. Not to mention Doug Ross, who produced some of the most popular MTV and Bravo reality shows through Evolution Media, including The Hills and Vanderpump Rules.

On the other hand, Nussbaum showcases how representation of racialized people in the genre has been much more problematic, particularly in early series that were especially harmful in reinforcing stereotypes. Nowhere was this representation as damaging as it was on the ‘90s Fox series COPS. This program, which was also influenced by cinema vérité and is now seen as copaganda, filmed real police officers responding to 911 calls and making arrests, often against racialized people.

Nussbaum also notes how Black cast members were particularly tokenized in the first seasons of both The Real World and Survivor. Black cast members like Kevin Powell, Gervase Peterson and Ramona Gray were portrayed as starting conflict when they were simply responding to racist behaviours, and were more often portrayed as lazy compared to white contestants. Still, Nussbaum showcases how Peterson and Gray were key former contestants who advocated for Survivor’s 2021 diversity initiative, where a minimum of 50% of the cast and 40% of the crew are BIPOC.

Another major theme Nussbaum explores is that of exploitation and labour, which are arguably the biggest criticisms levied against the genre as a whole. While Hollywood film and television production is a uniquely unionized American industry, reality television has often been a way to skirt around union-made programming. For example, shows like COPS emerged during the 1988 WGA strike, when no new narrative series were being produced.

Since reality show stars and crew members don’t fall under the Hollywood unions, labour practices have historically been quite horrific. Even though reality contestants are usually compensated for their appearances these rates are very low. Likewise, working conditions for crew members are notoriously brutal, including long hours and chaotic working conditions. For example, Nussbaum details how the first season of Survivor didn’t have a plan to house camera operators until they started filming.

Nussbaum also shows how crew members have been forced to manipulate cast members into getting the on-camera reactions needed to fulfill produced storylines. She devotes a significant section of the chapter on The Bachelor to interviewing Sarah Gertrude Shapiro, a former field producer of the series who admitted to using cruel techniques to make women on the show purposefully cry on camera. (Shapiro is also famous for later turning her work experience on the franchise into the fictional series UnREAL.)

Still, Nussbaum shows how cast and crew members have fought back against these exploitative practices, with historical examples such as the cast mutiny during the first season of Big Brother, as well as collective efforts in the mid-2000s for reality crew members to join the WGA and IATSE. Sadly, these negotiations failed and reality television work remains non-unionized for both cast and crew.

Even though the book is incredibly strong, it does have minor weaknesses. While most of the chapters focus on just one show, some of the chapters combine many programs, which I felt personally reduced the impact of their specific histories.

For instance, the chapter “The Wink” covers Queer Eye for the Straight Guy, The Real Housewives of Orange County, Project Runway, Keeping Up with the Kardashians and RuPaul’s Drag Race all in under 30 pages. To me, combining all these historic programs waters down their influence, particularly Real Housewives and Drag Race, two monumental franchises that are reduced to mere pages.

Another weakness of the book is that it ends around 2007. While Nussbaum was likely constrained in scope, reading about reality programs that flourished during the social media era would have made for a more holistic analysis of the genre’s legacy and reputation. For example, while Nussbaum briefly alludes to the Kardashians, their show would have made a great separate chapter, especially given the book’s throughline of connecting reality shows of the aughts to our current cultural moment.

Despite these minor criticisms, Cue the Sun! is exceptionally well-researched and extremely readable. It makes a very convincing argument that reality television should be taken seriously as a genre, a thesis that will even sway readers who aren’t already fans.

Still, obsessives are likely to get the most out of this rich text, as most airtime is devoted to five shows: The Real World, Survivor, Big Brother, The Bachelor and The Apprentice. If you’re a true devotee of any of these programs or love to read about TV history, then Cue the Sun! is the perfect addition to your summer reading pile. Why out!

Enjoyed this newsletter? Tip me a coffee, like and comment, or share it with a friend!

Buy my novella Amy of Suburbia in paperback and PDF download here.

Follow me on Instagram, Goodreads and Letterboxd.