Do What You Love and You’ll Still Work Every Day for the Rest of Your Life

On Work Won’t Love You Back by Sarah Jaffe and Can’t Even by Anne Helen Peterson

“Our current “best practices” for achieving middle-class success: Build your resume, get into college, build your resume, get an internship, build your resume, make connections on LinkedIn, build your resume, pay your dues in a soul-sucking low-level position you’re told to be grateful for, build your resume, keep pushing, and eventually you’ll end up finding the perfect, stable, fulfilling, well-paying job that’ll guarantee you a place in the middle class. Of course, any millennial will tell you that this path is arduous, difficult to find without connections and cultural knowledge, and the stable job at the end isn’t guaranteed.”

- Can’t Even by Anne Helen Peterson

I spent a long time thinking I needed a perfect black blazer. It was an article of clothing that reappeared over and over again on lists of essential pieces to own, a building block of the working woman’s wardrobe, an “investment” item. I spent months, nay, years, hunting one down, since I was never satisfied with what I could find at the thrift store, all of the proportions wrong, all of the silhouettes unflattering.

My perfect black blazer finally came to me at my retail job at a high-end women's clothing store. It was long, but not overwhelmingly so on my torso, with an open-front and two patch pockets. It was made out of Tencel, a soft and sustainable fabric that felt luxurious to the touch. It was also expensive, the cost equivalent of 18 of my working hours, three full shifts. I waited for a sale and, combined with my work discount, bought it for half-price.

Once I had it, I never wore it. It was too formal for the day-to-day work of helping customers and running up and down the stairs to the store’s inventory. And whenever I tried to wear it in public, I felt overdressed. I thought that surely I would need it when I got an office job. But once I had my one and only 7-week stint in a cubicle, the company’s dress code was depressingly casual. All this work to find the perfect black blazer–a symbol of professionalism and wealth that I internalized as a must-have–and I had no actual need for it in the day-to-day reality of my life.

Two recent non-fiction books take on these kinds of myths of the modern working world, many of which are far more insidious than what clothes to wear. In Can’t Even: How Millennials Became The Burnout Generation by Anne Helen Peterson, the ex-Buzzfeed reporter expands on her infamous essay on millennial burnout, a phenomenon caused by the ever-declining social security net and an ever-increasing wealth gap. In Work Won’t Love You Back: How Devotion to Our Jobs Keeps Us Exploited, Exhausted, and Alone journalist Sarah Jaffe, who was one of the first reporters to cover Occupy Wall Street and the Fight for $15, examines how jobs referred to as “labours of love” keep workers in a state of constant stress, fatigue, and fear.

Although there are quite a few statistics to back Peterson’s claims, Can’t Even is written anecdotally from a social sciences point-of-view, including personal pieces from the author about her own relationship with millennial burnout. The book is divided into nine chapters, each touching on some aspect of how generational wealth inequality and stress have become absolutely out of control for millennials and their younger cohort, Gen Z. The book was published in September 2020, meaning that its COVID-19 analysis is relegated to the introduction, stating that everything touched on has only been magnified during the pandemic.

Can’t Even starts by describing how work has actually always been pretty bad. As Peterson writes, “Before the Great Depression, that was the American way: abject insecurity for the vast majority of the country.” In truth, it is only an illusory generational fluke that work and wealth was easier for (mostly white, mostly male) boomers and Gen Xers to come by, whether it was the lower cost of tuition for higher education in the ‘70s or the growth in white-collar jobs prompted by technological advances in the ‘80s and ‘90s.

Still, a lot of millennials faced a higher-pressure childhood than most boomers and Gen Xers did, a phenomenon that Peterson refers to as “concerted cultivation”: a middle-class pastime to guarantee a child’s “strong” future by getting them started early in music, sports, art, dance and other organized activities. This was (and still is) done to stack the potential resumé of a literal child, all in service of eventually going to college and landing a “good” job.

But, as Peterson notes, a “good” job is still just that: a job. And even for those who do something “cool,” the pressures of trying to keep a work-life balance is much harder than it once was, due to constant availability through email and text, even when one is technically off the clock. As she writes, “Barring a significant, psychology-altering intervention, once someone equates “good” work with overwork, that conception will stay with them–and anyone under their power–for the rest of their lives.”

Peterson also debunks the prevalent generational myth that most workers work Monday to Friday from 9 to 5, when in reality, those people are in the minority. In truth, 31% of full-time employees and 56% of people with multiple jobs work on the weekends. And due to the rise of neoliberalism, the decimation of social services, and out-of-control housing markets and rental prices, the majority of people–both young and old–are forced to work multiple jobs and freelance gigs just to make ends meet, a situation that becomes even more precarious if one has children.

More myths surrounding work are debunked in Work Won’t Love You Back by Jaffe, who has a long career of writing about social issues and labour movements (the book’s tone is much more focused on reporting from a labour history standpoint than the social sciences/personal one of Can’t Even). Since it was published in January, the book also includes a fair amount of COVID-19 analysis, along with an examination of the protests for racial justice spurred by the murders of a number of unarmed Black US citizens, including Breonna Taylor and George Floyd.

All the jobs in Work Won’t Love You Back are what are referred to as “labours of love.” In the first section, Jaffe tackles occupations done out of “love” for those they serve, such as teachers, domestic work, and nonprofit workers. In the second part, Jaffe takes on occupations done for the “love” of the job itself, like artists, video game developers, and professional athletes. Each chapter starts with a real-world example of a person working in that industry, before diving into the history behind that form of labour, and ultimately ending each chapter with how the person fought back against the inequities of the system. Work Won’t Love You Back also shows how the inequalities of most of the jobs Jaffe covers are both feminized and racialized, making it a more intersectional analysis of work than the average labour tome.

My favourite sections of the book were those that focused on internships and academia. While higher education might have once been a one-way ticket to the middle-class, the neo-liberal operation of the university makes that no longer the case. In the chapter on internships, Jaffe describes how internships are now often a program requirement to graduate, but in reality, allow for the university to reduce its teaching costs while getting students to perform free labour for a grade. Likewise, Jaffe notes that while becoming a professor was once a guarantee of job security, the rise of hiring only temporary adjunct professors forces academics to teach multiple courses at multiple schools, classes that could be canceled at any time, without providing any health benefits.

As a 25-year-old writer working retail, I was particularly struck by Jaffe’s use of the term “hope labour”: work done, often for free, with the intention of it leading to paid opportunities. How to balance my unpaid “passion” labour (writing and music) with paid “unpassionate” labour has been a constant struggle since I graduated from university four years ago, as it is for most people with a skill or dream that doesn’t translate into immediate wealth. And, of course, things have only gotten even worse in the pandemic, not only for me, but for many people who work in the service or gig industries, or are self-employed. While it was a blessing to receive CERB last spring and then be able to go on EI, it has also been extremely stressful, from navigating the very confusing bureaucracy of it to not knowing how much I would eventually have to pay back or even the end date of my benefits.

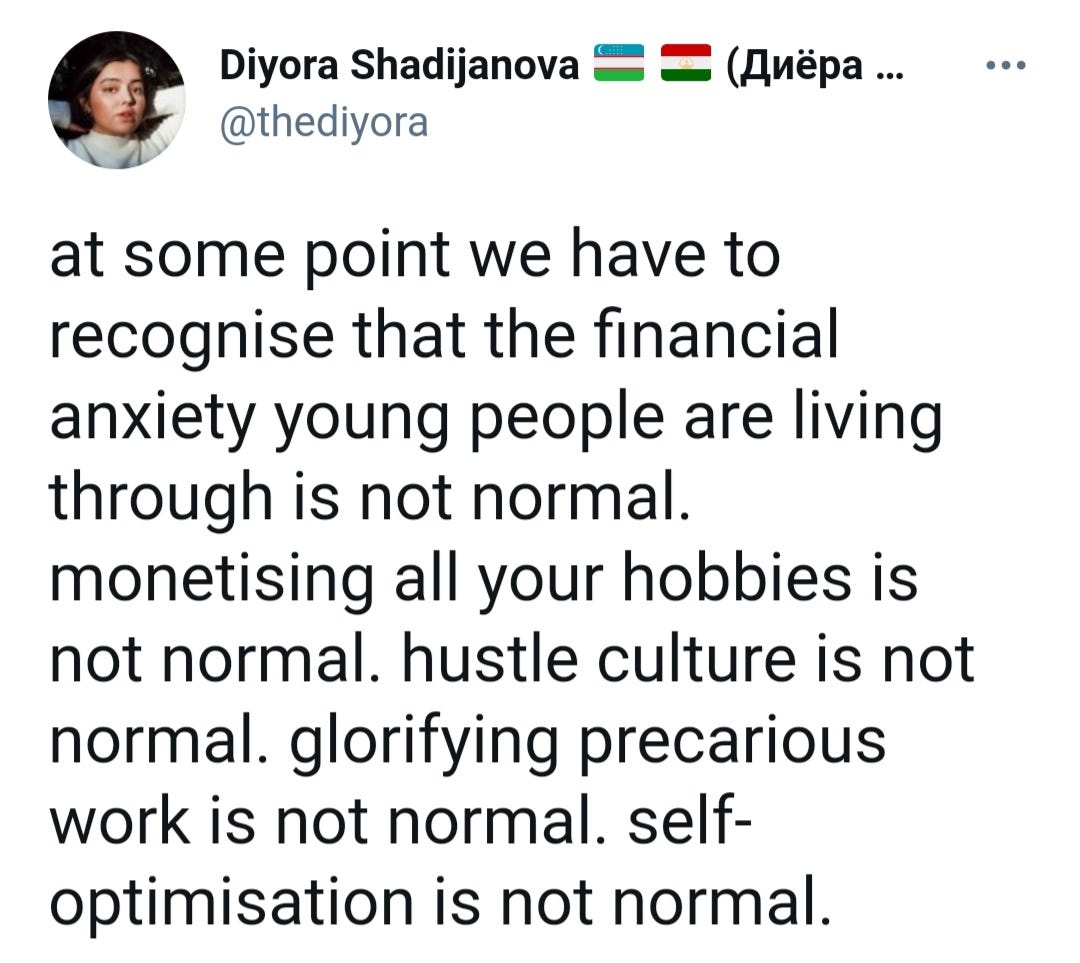

Both Peterson and Jaffe note that the effects of late capitalist burnout are real, on our wealth, health, and personal relationships. As Jaffe writes, “When our relationships fall apart, we still blame ourselves, rather than looking at all the social, institutional pressures that made it nearly impossible to continue them. Love is still just another form of alienated labour.” So what is the solution to the crisis of late capitalism? From an individual standpoint, it feels like there is not that much to be done, especially when all of the problems like low wages and increasing rent, grocery, and living costs are systemic and out of reach for the average millennial or Gen Z worker to change. As Peterson notes, “No amount of hustle or sleeplessness can permanently bend a broken system to your benefit.”

However, all of the people profiled in Work Won’t Love You Back organized to fight back against their work conditions. If we can’t change things in our workplaces individually, we can (try to) change them together, whether through asking our co-workers how much they make so that we can know if we are being undervalued, calling out discrimination or oppression when we hold privilege or seniority, advocating together for collective needs in the workplace, forming a union, or striking.

Likewise, there are personal adjustments we can (try) to make on our own, to the best of our abilities and as our circumstances allow, to resist the psychic effects of late capitalism. We can let go of perfectionism in the workplace, resist the “rise-and-grind” attitude, and try not to monetize (all of) our hobbies. Instead, we can try to let ourselves enjoy things just to enjoy them, try to let ourselves rest when we are tired, and try to make time for what really matters in life, even when it feels impossible.

What Else I’m Reading: I recently finished Danielle Evans’ 2020 short story collection The Office of Historical Corrections and loved it! I was really struck by how character-driven, subtle, and nuanced each story was in such a limited number of pages. You can read two of the best stories, “Boys Go To Jupiter” and “Anything Could Disappear,” online.

What I’m Watching: Speaking of millennial burnout and perfectionism, I finally watched the 2010 Darren Aronofsky film Black Swan, starring Natalie Portman as an unhinged ballerina. “Woman Slowly Losing Her Grip On Reality But Also Maybe She Never Was Living In Reality To Begin With??!!” is literally my favourite narrative, so it was a five-star watch for me.

What I’m Listening To: Somehow I missed that one of my favourite poets and music writer sHanif Abdurraqib has a new podcast called Object of Sound. I really liked the episodes on Soul Train and Whitney Houston singing the US anthem. Also, Still Processing is back for another season, and each episode is killing it so far.

Mutual Aid Calls: A two-spirit Indigiqueer beadworker is looking to raise money for gender-affirming top surgery. You can support them financially either through their GoFundMe or online raffle.

Thanks for reading. If you liked this newsletter, please subscribe, like, comment and share. The next issue will be out around April 16. You can find me on Twitter, Instagram, Goodreads, and Letterboxd. Take care of yourself, and each other.

I really liked the Anne Helen Peterson book and am looking forward to reading the Sarah Jaffe one when my hold comes in! In terms of "interesting thoughts about jobs", I'm also reading Dean Spade's book on mutual aid right now, which has lots of good stuff about nonprofits, and the nonprofitization of social movements, that is extremely relevant to (and deeply indicting of) my particular work situation. Always a delight to see your newsletter in my email. <3

I like to remind people that I don’t “love” what I do: I do what I do because it’s simply what I do, what I can do, what I can’t NOT do, what I’d die if I couldn’t do... I am not good at much else, though I can pretty much pick up any day job and do it well for a couple years before it drives me crazy. Nevertheless, what I do is always work, it’s not something I can afford to do for free, and I always want to cringe when people say that thing about doing what you love meaning you’ll never work a day in your life. Work is beautiful! Employment, not always, in fact, more and more rarely. There is a difference, often, between work and employment, that always bears pointing out.

When people say, oh you’re a cartoonist, what a fun job that must be, they’re really showing a total lack of understanding of that difference. You know what’s fun? Being overpaid! That’s fun! I love it when that happens!