Content Warning: This week’s newsletter dives into a spoiler-free review of A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara. The book tackles a variety of difficult subject matter, most notably sexual violence and self-harm. I refer to these topics in passing in my review but do not describe any scenes in detail. If you would prefer to skip this newsletter, I totally understand. I’ll be back with a more light-hearted “Obsessions” newsletter next week.

There’s a popular list on the social film-review website Letterboxd called “You’re not the same person once the film has finished.” The list of 293 films features movies both visually brutal (Climax, Dogma, Mother!) and emotionally resonant (Lady Bird, Before Sunrise, In The Mood For Love). Basically, it’s a career retrospective of David Lynch, Wong Kar-wai, and the Safdie brothers.

There’s a less clear version of this list as it applies to contemporary books. While there are many novels that have moved me, there are only three books from my recent memory that I finished and felt completely stunned by: Eileen by Ottessa Moshfegh, Darryl by Jackie Ess, and Beloved by Toni Morrison.

Then I read Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life.

A Little Life has a notorious reputation on Bookstagram and BookTok. The book defies the meaning of a content warning, diving deeply and brutally into subjects such as child abuse, self-harm, sexual violence, kidnapping, pedophilia, and suicide. Most reviews come with a heavy warning to not read the book if you’re in a bad headspace, with many reviewers writing that they’re unsure if they should even recommend the book to others at all.

Despite this, A Little Life is an extremely popular read. Although it was published six years ago, there are 43,0000 people currently reading it on Goodreads alone. By comparison, Sally Rooney’s Beautiful World Where Are You, a blockbuster book released two weeks ago, has 14,000 users reading it currently.

The other thing that stands out is the novel’s length. At over 700 pages in hardcover and 800 in paperback, A Little Life is the definition of a tome. While the average novel ranges from 80,000 to 120,000 words, the word count of A Little Life is approximately 375,000. As a fast reader, I can finish a book in three to four hours: A Little Life took me 16.

In spite of its horrific subject matter and Biblical length (or perhaps because of it), A Little Life was released to universal critical acclaim when it was first released in 2015. Yanagihara placed as a finalist for that year’s National Book Award and Man Booker Prize, and won the widely-respected Kirkus Prize, despite the fact that both she and her editor thought that the book would not sell well due to its content.

As a dedicated reader and fan of queer contemporary fiction, I avoided A Little Life for a long time. It’s one of my friend’s most-hated books of all time. The novel never fails to stir up Discourse when Gay Writes does an Instagram story prompt.

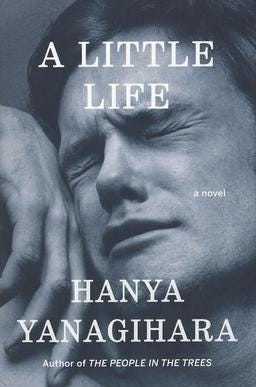

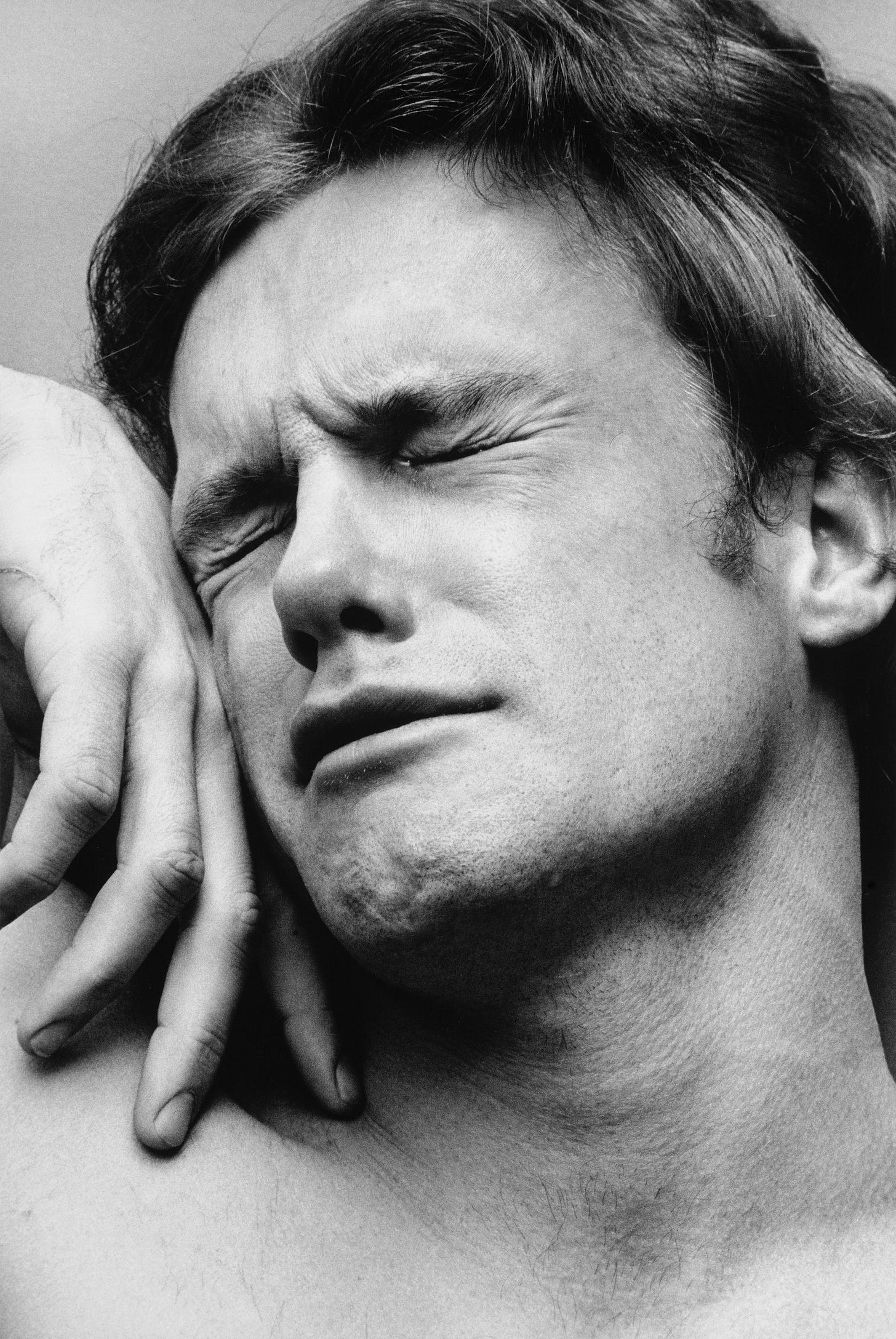

Still, the book’s cover — a black-and-white photo of a face titled “Orgasmic Man” taken by gay photographer Peter Hujar — started to become absolutely unavoidable on my Explore page. I decided it was time for me and my morbid curiosity to see what all the talk was about.

The first thing that struck me about A Little Life was the quality of the writing. As a frequent reader, it’s very rare to be stunned by a book on the sheer level of its prose: the last time I felt as gripped by sentences was reading Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Novels in 2018.

The first hundred pages of A Little Life are gripping and moving, telling the backstory of three college friends — Willem, JB, and Malcolm — pursuing artistic careers in New York City. As the novel progresses, more terrain is covered, spanning multiple years and points of view. Each character is richly detailed, with plentiful backstory.

As a writer, I was struck with the specificity with which Yanagihara created the character’s lives, from describing the fictional-yet-completely-believable plays and films that Willem acts in throughout his years as a celebrated actor, to the exhibition and individual painting titles in each series described for JB’s visual art career.

Likewise, each apartment and space the friends inhabit is so comprehensively and intricately described that the reader truly comes to know the spaces they’re reading about, in addition to the characters who live in them. It’s not usual to see this level of world-building in literary fiction when the world depicted is often realistic and as such, taken for granted.

And yet, it’s only about a chapter in, when the characters start to dive deeper into their relationship with their mysterious friend, Jude St. Francis, that the novel starts to descend into what can only be described as hell.

The majority of A Little Life’s 700+ pages are devoted to unraveling the extreme abuse Jude endured growing up as an orphan taken in by a monastery, as well as the intimate partner violence he experiences in his adult life. To cope with his trauma, Jude self-harms by cutting himself with razor blades, the descriptions of which are frequent and detailed. Even during the happier sections of A Little Life, when things are going well for Jude, it is difficult to not feel your stomach churn, waiting for the brutality to come.

These descriptions of trauma, abuse, and violence are the core of what Yanagihara was attempting to do with A Little Life as a literary project. In an interview for Vulture, Yanagihara said she wanted to write a book where nothing good happened to the main character and that they were unable to stop their suffering. As she stated,

“One of the things I wanted to do with this book was create a protagonist who never gets better. I also wanted the narrative to have a slight sleight-of-hand quality: The reader would begin thinking it a fairly standard post-college New York City book (a literary subgenre I happen to love), and then, as the story progressed, would sense it was becoming something else, something unexpected… One of the ways I’d always described the book (to my editor and to my agent) was as a piece of ombré cloth: something that began on one end as a bright, light bluish-white, and ended as something so dark it was nearly black… I wanted A Little Life... to begin healthy (or appear so), and end sick — both the main character, Jude, and the plot.”

It’s worth noting that there is power in stories like these, to make space for people who’ve survived violence. Depictions of violence in books and film may not always be triggering to survivors; sometimes, exploring this kind of subject matter can, in fact, be healing. For instance, David Lynch’s Twin Peaks prequel Fire Walk With Me found an audience with incest survivors, who praised the film. According to Wikipedia, Laura Palmer actress Sheryl Lee said, "I have had many people, victims of incest, approach me since the film was released, so glad that it had been made because it helped them to release a lot."

The flip side to this is that excessive depictions of violence can more frequently come across as exploitative, particularly when it comes to who is doing the depicting. Yanagihara stated that for A Little Life, she was interested in exploring the impact of trauma on a person’s life and those around them, and was influenced greatly by the trauma experienced by a childhood friend.

The trouble with the novel’s depiction of abuse and violence is that it becomes harder and harder to stomach as the book goes on due to the sheer magnitude of what Jude endures in his life. That’s not to say that certain people don’t experience horrific levels of abuse, but the brutality with which Yanagihara depicts multiple rape and self-harm scenes at times feels excessive, particularly as the novel progresses, with some moments feeling more akin to trauma porn than a nuanced depiction of the effects of trauma on a person’s life.

The other criticism that plagues A Little Life is that it’s one of the most popular queer stories of the 21st century, tackling a love story between gay men, and yet the author is a (presumably) straight woman. Like Call Me By Your Name, it’s another instance of a blockbuster queer story being devoured by a mass straight audience to critical acclaim, but not being told by an actual queer writer. Additionally, the novel — inadvertently or not — furthers the stereotype of gay men as victims of childhood sexual abuse. All of these factors lead queer audiences to seriously question it for being heralded as the “great gay novel” of our time.

Another surrounding factor of A Little Life is its cult of fandom. The book’s official Instagram features readers taking selfies with the book’s cover over their faces, as well as posing with t-shirts, tote bags, and mugs that say “Jude&JB&Willem&Malcolm” (some photos are even both at once). There are also images of A Little Life-inspired embroidery, as well as fan tattoos, the most popular of which are Jude’s name and the axiom “x = x.”

I think it’s fine to love a book so much that you want to buy a t-shirt, or even get a literature-inspired tattoo. But for a book depicting extreme violence, reducing it to merch seems weird to me. Even memes about the novel feel uncomfortable for what the subject matter takes on. The “x = x” tattoos strike me as particularly upsetting, since this is what Jude is thinking during a moment of brutal intimate partner violence, and equates to how he will always be a victim of abuse.

Yet, for all of its controversies, A Little Life is a reading experience like no other. It’s engrossing, painful, and stomach-churning. It’s also exquisitely written, and the relationships between the characters are filled with love in spite of the brutality. As soon as I finished it, I was glad I read it (I also couldn’t stop crying). It is one of the most singular reading experiences of my life.

However, as the week since I finished it has passed, I can’t help but feel the remains of a bad taste in my mouth. I remember some of the violence and abuse described, and my stomach churns anew. On certain days, it feels like several scenes in A Little Life were no more than exploitation, meant to see how far Yanagihara could take both the character and the reader, ethics be damned (I had the same feeling watching Climax by Gaspar Noé earlier this year). Even if a piece of art can take you to that level, it doesn’t always mean the artist should have gone there.

I wouldn’t recommend A Little Life to anyone who is just a casual reader. If you only read a handful of books a year, you probably don’t need to make this novel one of them. But if you’re interested in reading characters in an intimate way and seeing what the depths of writing can be pushed to, you might just have to pick it up and see for yourself.

Thanks for reading! The next newsletter comes out next week. Make sure to subscribe to never miss a newsletter and to like, comment, and share it if you enjoyed it - it really helps me find more people interested in my writing. You can find me in the meantime on Goodreads, Letterboxd, Twitter, and Instagram.

honoured to have a cameo as "friend who hates this book" 💜

I had a really hard time with this book when I read it a few years ago. But your review has me wondering if I read it at the wrong time. Would I respond differently now? Maybe I’ll reread it, or try another of her books. Thanks for this review and for the food for thought!